Artist

Jacob de Wit, (baptized December 19, 1695, Amsterdam, Netherlands—died November 12, 1754, Amsterdam), Dutch painter and draftsman who worked primarily in Amsterdam and was known for his Rococo-style ceiling paintings and masterful grisaille works, some of which could still be viewed in the twenty-first century in their original locations.

De Wit began his art studies at age 9 as an apprentice to Amsterdam painter Albert van Spiers, with whom he stayed until age 13. He continued his studies in Antwerp with the financial support of his uncle, an art dealer. De Wit attended the Royal Academy in Antwerp from 1711 to 1713 and in that time honed his drawing skills and began his lifelong study of Peter Paul Rubens, whose works could be found in religious and public buildings throughout that city. Rubens remained the single most influential artist for de Wit. De Wit made copies of many of Rubens’s works, notably Rubens’s ceiling paintings in the Jesuit church in Antwerp, now St. Carolus Borromeus Church. His original set of copies was destroyed by fire in 1718, though de Wit made a second, more-finished set that was later reproduced as engravings. Over his lifetime, he amassed a large art collection, including numerous works by Rubens, some by Anthony van Dyck, and others by Dutch and Flemish contemporaries and old masters. In 1713 de Wit joined the Antwerp Guild of St. Luke.

About 1715 de Wit returned to Amsterdam, where he forged an important relationship with Father Aegidius de Glabbais, a Roman Catholic priest of the schuilkerk, or hidden church, of Moses and Aaron. In 1716 and over the next few years, he painted several works, including an altarpiece for the Moses and Aaron schuilkerk, an altarpiece titled Baptism of Christ for Het Hart schuilkerk, now Museum Ons’ Lieve Heer op Solder, and a portrait of Father de Glabbais in 1718.

From the 1720s onward, de Wit enjoyed a steady stream of commissions, public and private. He created many ceiling and wall paintings into which he incorporated grisaille, gray and white paintings that give the illusion of three-dimensionality, or bas-relief. He called his grisailles “witjes” - a play on the Dutch word for “white” and his surname. Notable interiors include the Amsterdam Town Hall, now the Royal Palace, which he decorated with the monumental painting Moses Choosing the Seventy Elders,1737, and some 13 grisaille paintings of subjects from the Hebrew Bible. In 1738 he decorated the Alderman’s Hall of the Old Town Hall of The Hague with a ceiling painting framed by allegorical putti (Freedom, Industry, Temperance, and Fortitude) done in grisaille in the four corners. Other important works by de Wit were interior paintings for private residences, such as his series of five paintings of the story of Jephthah at the Amsterdam address Herengracht 168, a residence that in the twenty-first century operates as a theatre museum. Other private commissions include Flora and Zephyr, 1743, and Apollo and the Four Seasons, 1750, both created for homes along the Herengracht canal in Amsterdam. Drawings and oil studies for his interiors as well as canvases no longer in situ are found in collections throughout Europe and North America.

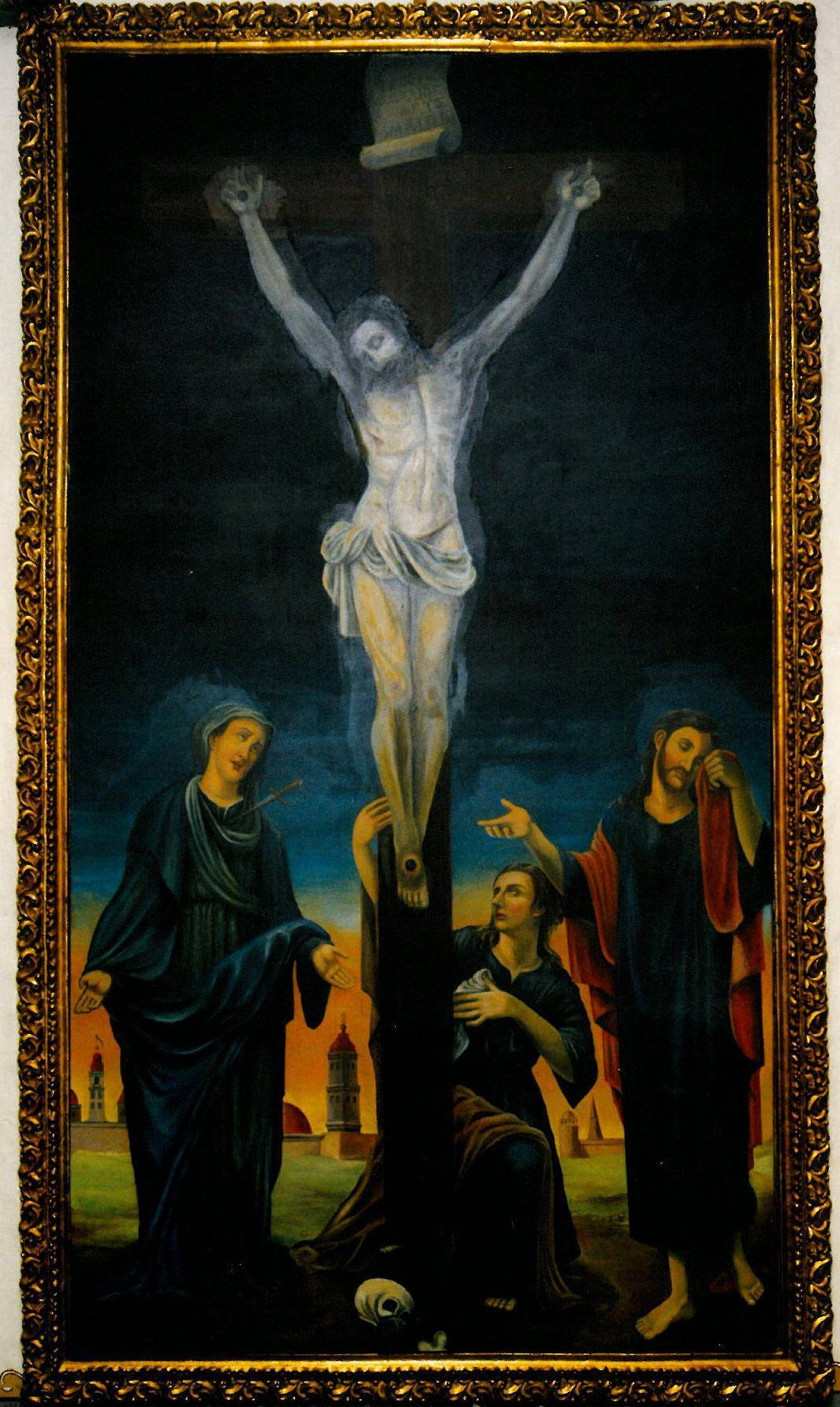

Extant Painting

Vanitas is an oil on canvas painting affixed to a masonite board and may have been originally commissioned as a wall accoutrement. The canvas edges are heavily eroded and craquelure and crazing is apparent throughout the work. Oval in shape, the painting is 12 1/2 inches in height and 9 inches in width or 32 cm by 23 cm. Signed J de Wit in usual motif of the artist and below dated 1732, both center left on the painting. The painting blacklights with minor retouch.

Provenance

The painting was acquired in or about 1910 by G.N. Northrop, Esq., a West Roxbury, Massachusetts attorney and subsequently by decent to family members until 2017 when it was acquired from Skinner Auctioneers in Boston in 2017 by The Mifflin Smith Collection. Northrop held an extensive fine art collection, inclusive of, an one example, Joaquin Sorolla y Bastida’s La Concha Beach, San Sebastián, 1906, held by the Clark Art Institute since 1984.

Few Dutch masterworks trace to earlier dates as record keeping in prior centuries was at best aberrant.

Vanitas Symbolism

A vanitas painting is a particular style of still life that was immensely popular in the Netherlands beginning in the seventeenth century. The style often includes worldly objects, inclusive of skulls, with the intent of reminding viewers of their mortality and the futility of worldly pursuits.

The word vanitas is Latin for "vanity" and that is the idea behind a vanitas painting. They were created to remind us that our vanity or material possessions and pursuits do not preclude us from death, which is inevitable. The phrase comes to us courtesy of a biblical passage in Ecclesiastes. In it, the Hebrew word "hevel" was incorrectly taken to mean "vanity of vanities." But for this slight mistranslation, the term would rightfully be known as a "vapor painting," signifying a transitory state.

A vanitas painting, while possibly containing many objects, always included some reference to man's mortality. Most often, this is a human skull, but items like burning candles and decaying flowers may be used for this purpose as well. Other objects are placed in the still life to symbolize the various types of worldly pursuits that tempt men. For example, secular knowledge like that found in the arts and sciences may be depicted by books, maps or instruments. Wealth and power have symbols like gold, jewelry and precious trinkets while fabrics, goblets and pipes might represent earthly pleasures. Beyond the skull to depict impermanence, a vanitas painting may include references to time, such as a watch or hourglass. To add to the symbolism, the symbols in vanitas paintings appear in disarray compared to other, tidy, still life art. This is intended to represent the chaos that materialism can add to a pious life.

Vanitas paintings were meant not only as works of art, they also to carry an important moral message. They are designed to remind us that the trivial pleasures of life are abruptly and permanently decimated by death. It is doubtful that this genre would have been popular had the Counter-Reformation and Calvinism not propelled it into the limelight. Both movements - one Catholic, the other Protestant - occurred at the same time as vanitas paintings were becoming popular. Like the symbolic art, the two religious efforts emphasized devaluing possessions and success in this world. They instead, focused believers on their relationship with God in preparation for the afterlife.

The primary period of vanitas paintings lasted from 1550 through around 1650. They began as still life scenes painted on the backside of portraits and evolved into featured works of art. The movement was centered around Leiden, a Protestant stronghold, though it was popular throughout the Netherlands and in parts of France and Spain. In the beginning of the movement, the work was very dark and gloomy. Toward the end of the period, however, it did lighten somewhat.

Considered a signature genre in Dutch Baroque art, a number of artists were famous for their vanitas work. These include Dutch painters like David Bailly (1584 - 1657), Harmen van Steenwyck (1612 - 1656), Willem Claesz Heda (1594 - 1681) and later Jacob de Wit (1685 - 1754). Some French painters worked in vanitas as well, the best-known of which was Jean Chardin (1699 - 1779).

Many of these vanitas paintings are considered great works of art today.